Overview

Problem.

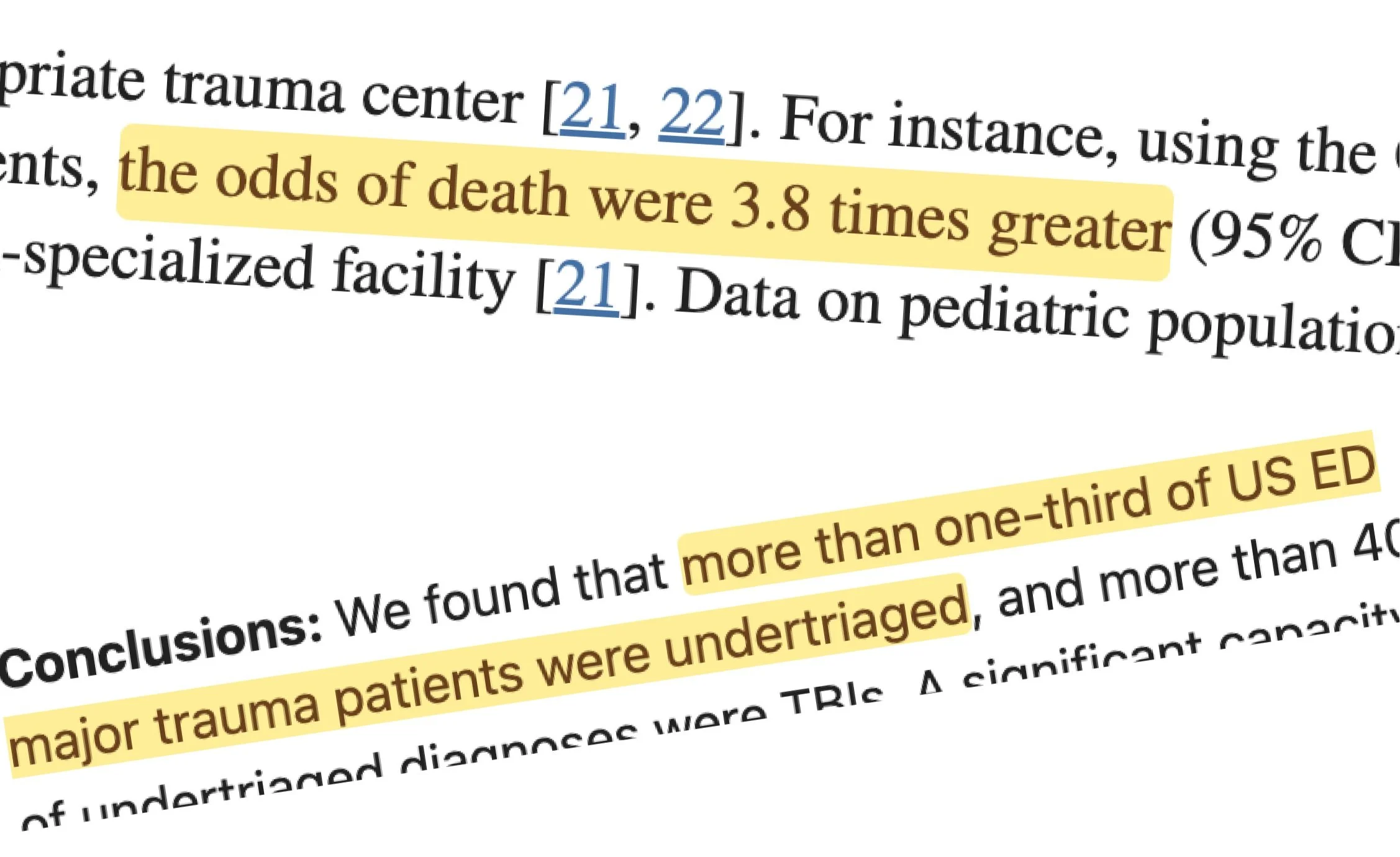

When a person gets severely injured, they sometimes end up in a hospital that doesn’t have the resources to treat them. The hospital then has to transfer of the patient to a higher level of care, a process called re-triage. When timely re-triage doesn’t happen, the odds of death are roughly 4x higher. Sadly, over 1/3 of U.S. trauma patients don’t get that treatment.

I worked with a research team from Northwestern Medicine to help Chicago hospitals transfer traumatically injured patients in a way that’s more timely and effective.

To better understand the problem, I conducted two on-site hospital visits. Our team saw firsthand how much physical documentation they are expected to reference as well as how physical distance can impede communication.

In-Hospital Visits.

User interviews

I led seven user interviews with nurses, health unit coordinators, and trauma coordinators to better understand the problem from users’ perspectives. I also crafted discussion guides to make the best use of our time with users.

Process Map

I then updated the 47-step process map that the team was using into a much more digestible 7 step process map that highlighted the areas of opportunity.

Insight

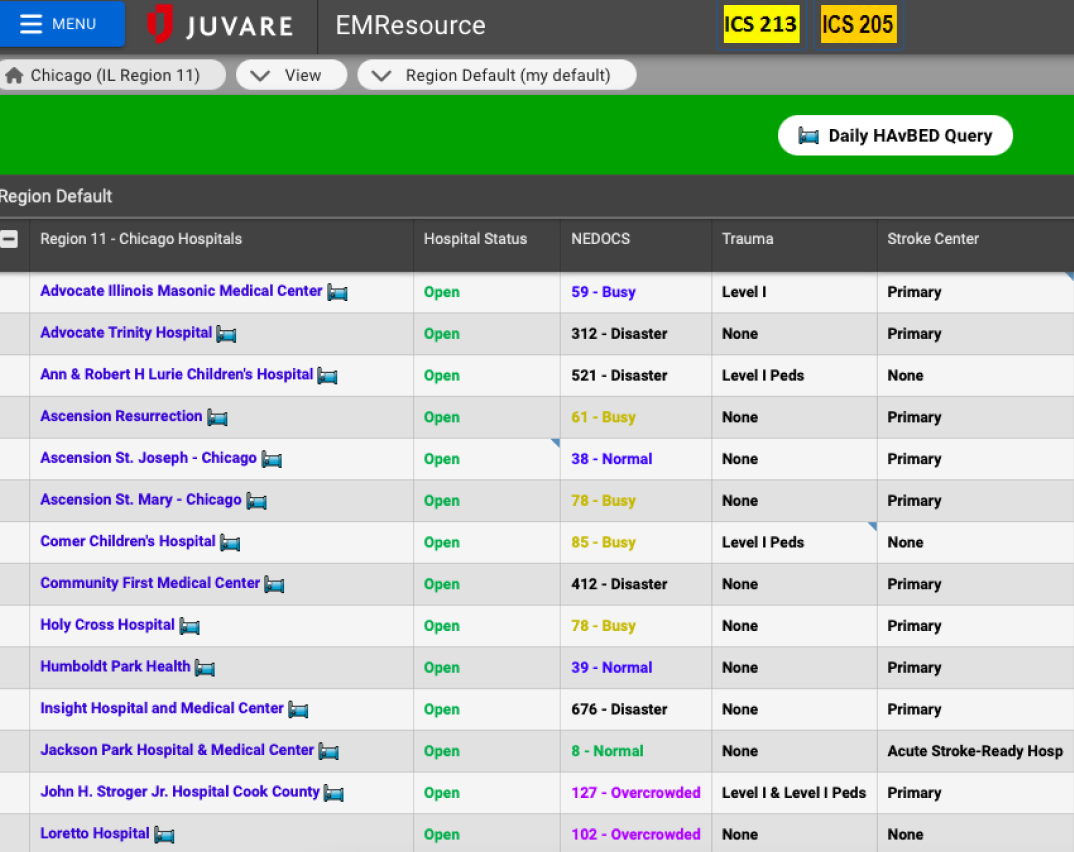

1. Users don’t consider current solutions reliable

2. Hospitals have vastly different cultures and workflows

3. Users suffer from information overload

How might we help Chicago hospitals find trauma centers that can accept their patients more quickly and accurately?

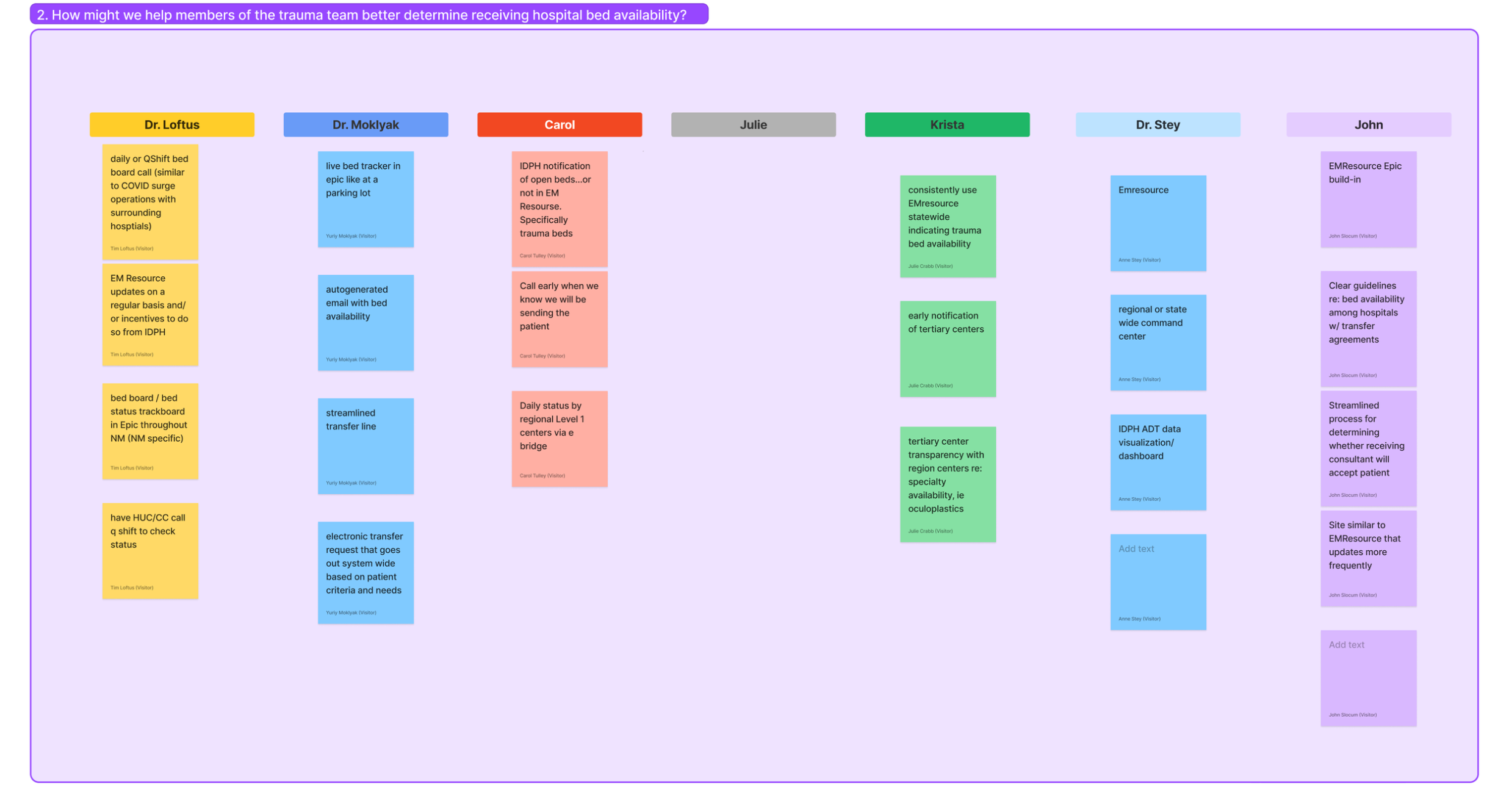

Co-design

I organized and led a co-design session in which doctors, nurses and administrators brainstormed 84 ideas to several prompts relating to how to improve bed capacity

Focus mapping

We then took the top 10 most prominent ideas from the co-design and subjected them to a two-dimensional ranking exercise where users took turns ranking concepts according to impact and desirability.

Storyboarding

I put together storyboards for each of the four top solutions that came out of the ranking exercise. We then presented these storyboards to the original users, who helped us narrow in on a final concept.

Prototyping

Version 1

For my first iteration, I made a rough sketch. I I included features that I thought made sense, such as a capacity percent, a time for when the tracker was last updated, and the ability to reserve a bed.

User Testing

Phase 1

Over the course of user testing, I spoke with 14 people. In this phase, I learned that automatically reserving a bed wasn’t feasible due to the fluid nature of the ER.

Prototyping

Version 2

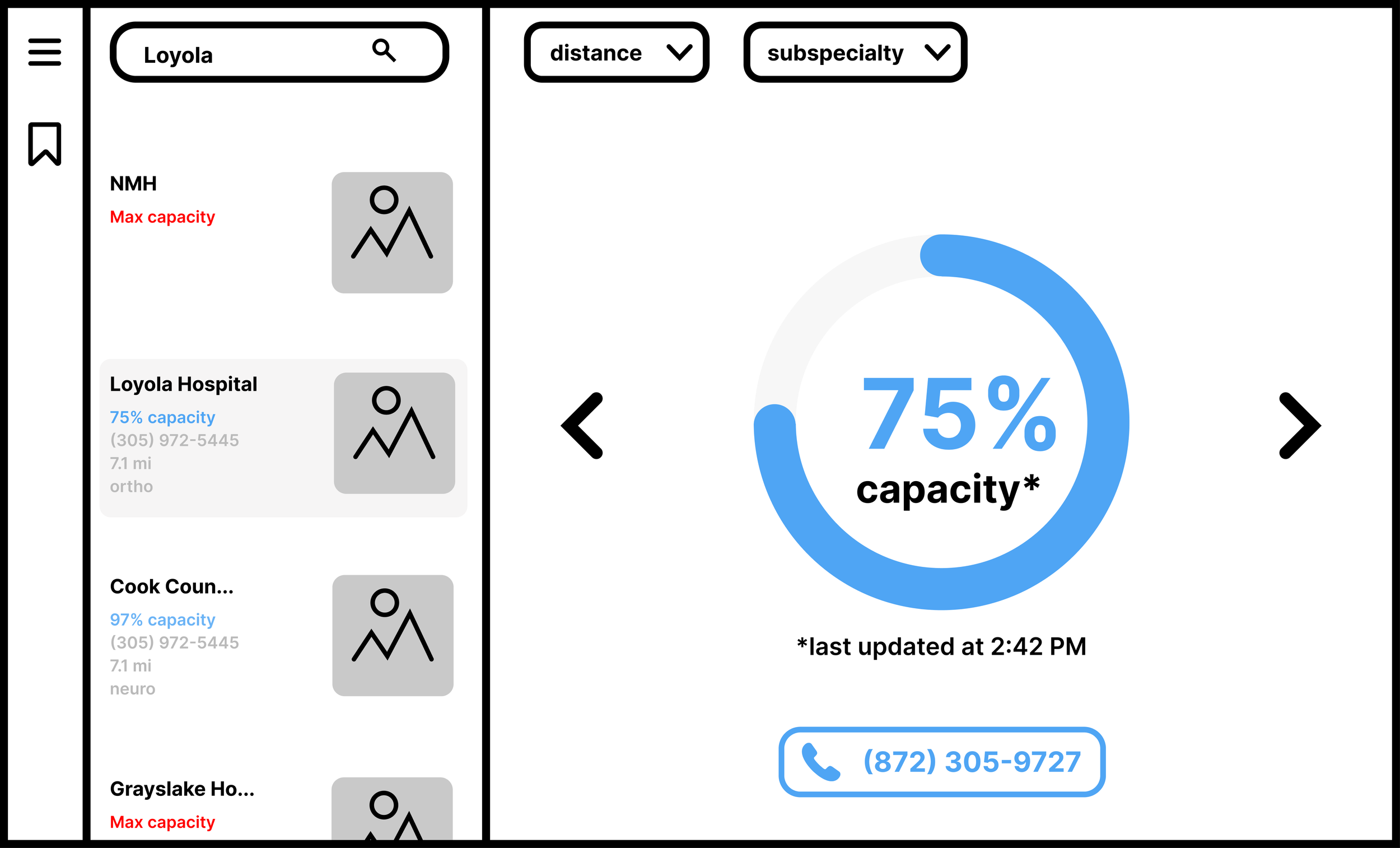

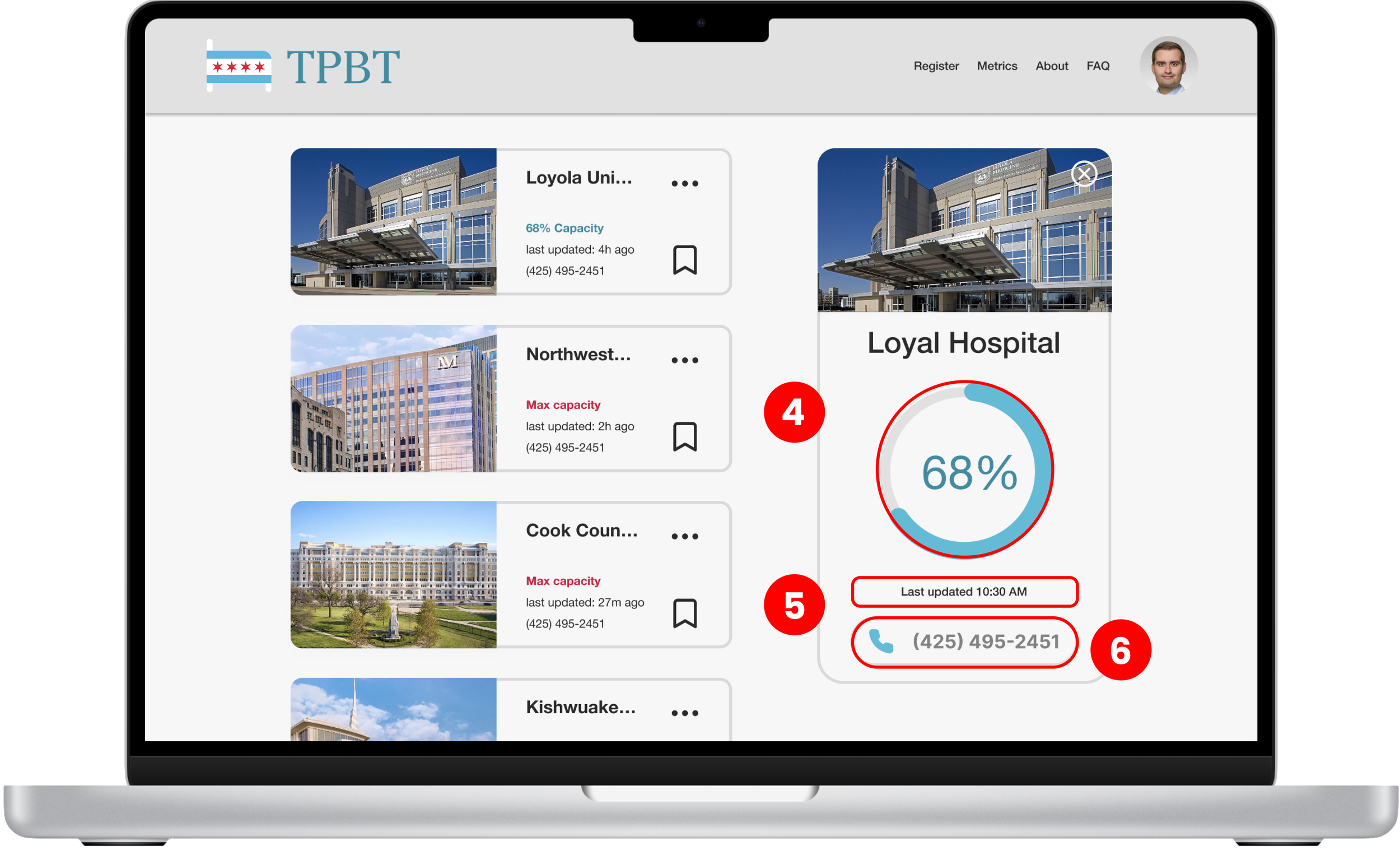

In response, I added contact information to the receiving center so that the sending center could confirm bed availability with a human, an important check in the re-triage process. I also upgraded the fidelity to a digital wireframe.

User Testing

Phase 2

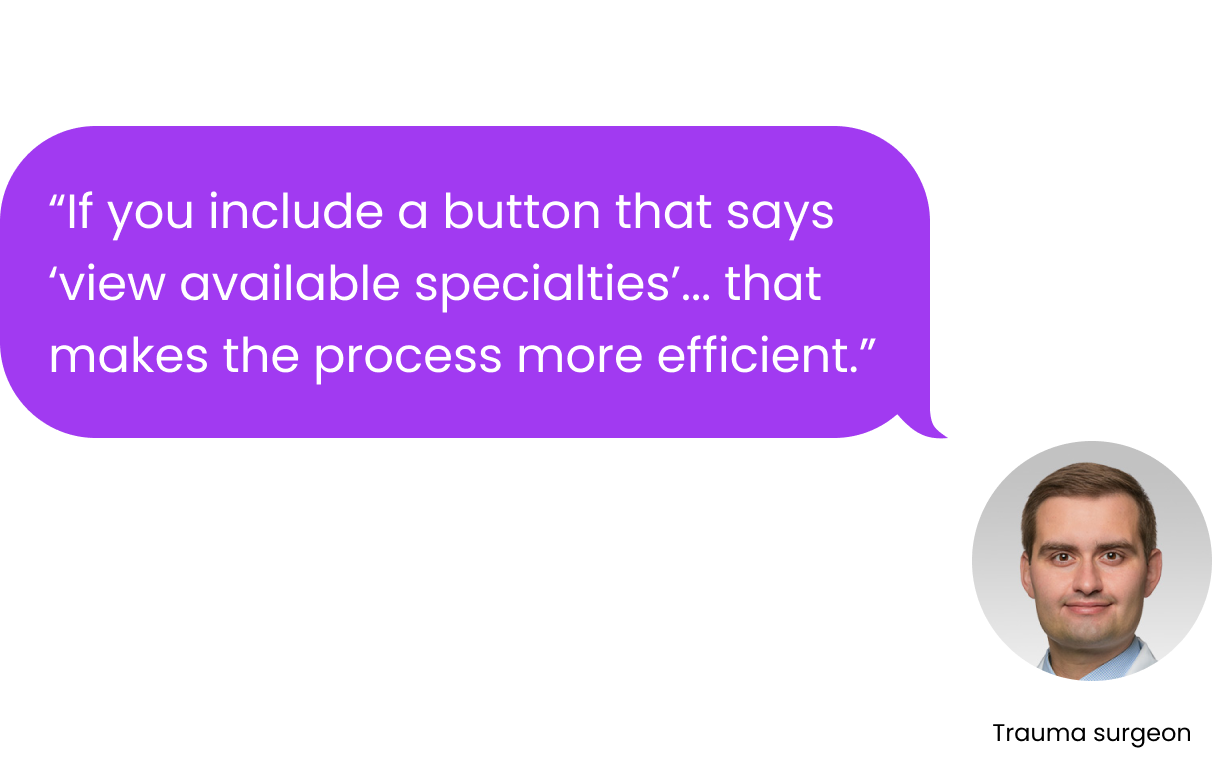

From more testing, I learned that users wanted to search by availability of common subspecialties like neuro and ortho. They also wanted to search by distance, because patients families don’t want to drive 2 hours to visit their relatives in the hospital.

Analogous Inspiration

At a certain point I realized that my design was starting to feel like the Uber and Open Table of trauma re-triage. I ended up basing the layout of my prototype on the UI of these company’s websites.

Solution

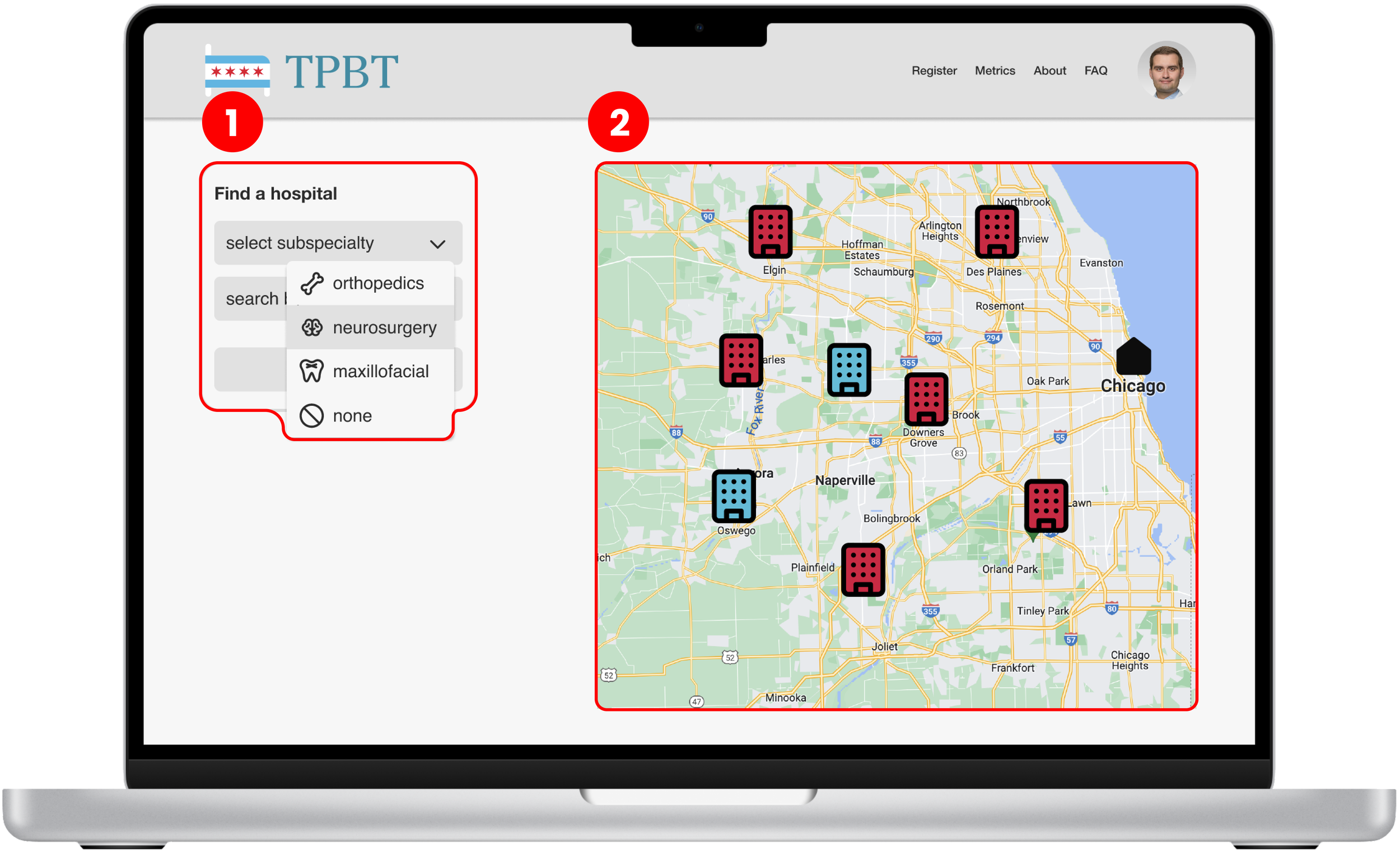

Search by subspecialty

Map view

List view

Bed capacity at-a-glance

Prominent “last updated” notice

Listed phone number for facility

Dark Mode

Partly because providers work late hours, partly because I want to stay up to date with UI best practices, I created a dark mode version of the bed tracker. This required building a design system and using tokens.

User Flow

Under the hood

Next steps

The project is currently entering the phase of high-fidelity wireframing. I have transitioned to an advisory role and handed off the project to a designer I trust. I am in the process of working with the research team to publish a paper for the Academic Surgical Congress as the lead author on how our team used human-centered design to address the issue of re-triage.

What I learned

Healthcare projects can take much longer than projected. Stay excited, but manage your expectations. It’s not the iPhone.

When working with colleagues who don’t have experience with design thinking, help manage their expectations by taking time to clearly explain the design process clearly. Reassure them that low-fidelity prototypes actually help de-risk the solution.

It’s very hard to get a hold of healthcare workers. That creates bottlenecks in research and user testing. Be thorough, systematic, and empathetic in your outreach efforts.

The titles of roles matter much less than what people say they do.

If there’s no agenda for a meeting you’re a part of, make one. Share it ahead of time, and be brief. Slides for agenda items help.

You don’t need to know what every word in a medical textbook means. You just need to know what people mean. At the same time, don’t pretend to know something you don’t. If you don’t know, say you don’t know.

Don’t put too much effort into the first iteration. Perfection is the enemy of the good.

I spent a lot of time learning how to sketch for this project. In retrospect, It would have been a better use of my time to double down on my Figma self-education while being OK with crappy v1 sketches (see above bullet).

The less you talk in user testing, the better. Ask clear questions and be brief. Imagine each word you used costs a quarter.

If I had a magic wand, I would follow a trauma re-triage in person from start to finish. Unfortunately, COVID-19 prevented this while I was in the research phase. Even after, HIPAA compliance and waiting around for a trauma re-triage to happen (a given ED sees less than one a day) made this extremely difficult.